Meet the 5 Extraordinary Louis Vuitton Finalists Who Are Reshaping Watchmaking

In an increasingly automated world starved of the human touch, the backstories of independent watchmakers have only grown more valuable and endearing.

Last year’s inaugural Louis Vuitton Watch Prize for Independent Creatives was a thrilling affair that brought the best out of contemporary watchmaking’s brightest minds. The grand prize ultimately went to the peerless Raúl Pagès, a veritable devotee of horology whose skills and creativity span the full breadth of mechanical watchmaking.

It comes as little surprise, then, that the second edition of this breathtaking competition has enthusiasts perched at the edges of their proverbial seats.

From the initial pool of submissions, 20 semi-finalists were selected by a committee of experts comprising 65 collectors and industry professionals. Their work was evaluated across five criteria: design, creativity, innovation, craftsmanship, and technical complexity.

This year’s jury includes watchmakers like Carole Forestier-Kasapi of TAG Heuer, Kari Voutilainen of Urban Jürgensen, and Matthieu Hegi of La Fabrique du Temps Louis Vuitton, alongside Monochrome founder Frank Geelen and Équation du Temps founder François-Xavier Overstake.

The five finalists will present their timepieces at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris on March 24th, 2026. The eventual winner will receive a €150,000 grant and a year-long mentorship with La Fabrique du Temps Louis Vuitton. Yet the honor of being crowned champion arguably outweighs the monetary reward.

It is no hyperbole to say that the watchmakers vying for this prestigious accolade have already made priceless contributions to the art. Neither is it a stretch to say that the lesser-known journeys behind these five brands—and how their struggles culminated in the creation of their out-of-this-world timepieces—are some of the most unique inspiring stories we’ve ever heard.

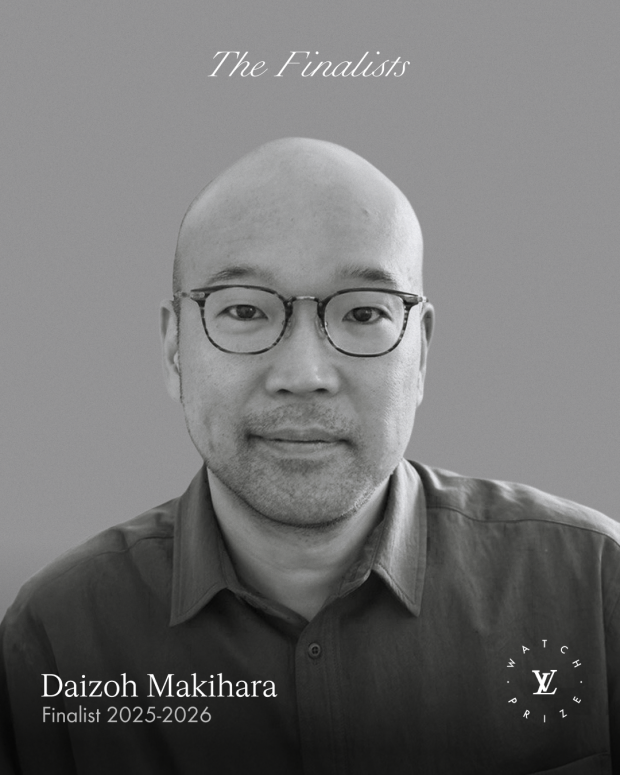

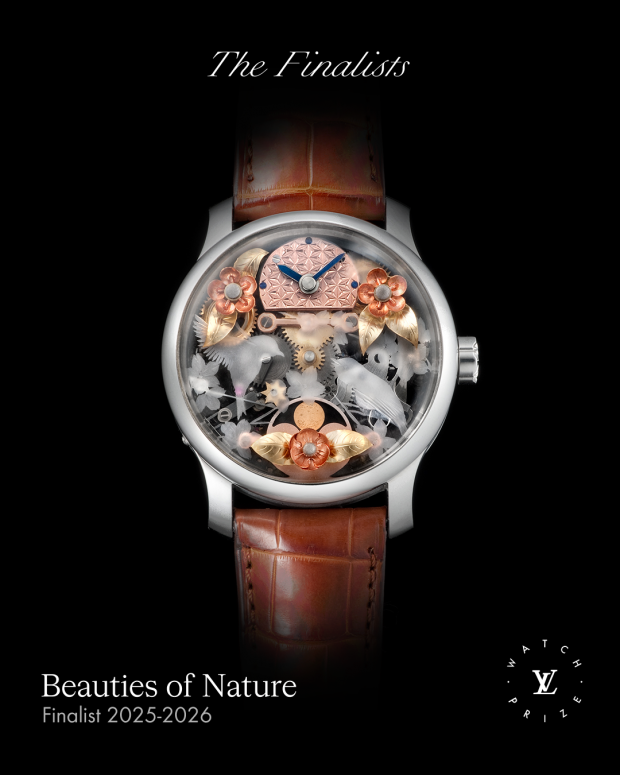

Daizoh Makihara of Daizoh Makihara Watchcraft

Praised by the god-tier Philippe Dufour, Daizoh Makihara is a former chef whose decision to attend jewelry college between 2006 and 2011 would quietly alter both his own life and the broader landscape of independent watchmaking.

When he finally found the courage to create his first watch in 2012, Makihara did something unprecedented. He introduced the ultra-intricate art of Edo Kiriko glasswork into traditional watchmaking. The technique—where skilled artisans cut patterns line by line, freehand, using a spinning diamond-sharp grinder—had never before been applied to watch dials. To this day, Makihara remains the only watchmaker to have done so.

His debut creation, the Kikutsunagimon Sakura (“chrysanthemum-linked coat of arms and cherry blossoms”), featured a 0.8mm-thin glass dial engraved using Edo Kiriko techniques to achieve a lace-like chrysanthemum motif. Housed in a 42mm pink gold case, the watch carried an asking price of ¥5.58 million—a reflection of both its bold spirit and near-impossible execution.

Makihara extends this devotion to detail beyond the dial. The plates of his Unitas movements are engraved with cherry blossoms, a deliberate choice reflecting his desire for his watches to embody Japan’s floral symbolism. The decoration does not stop there: the spaces between each sakura are finished with tremblage-style frosting, creating a subtle, shimmering texture.

Unsurprisingly, Makihara’s meticulous approach has purportedly resulted in a seven-year waiting list—one that is likely to grow longer should he emerge victorious in this competition.

His submission to this year’s competition is Beauties of Nature, a poetic objet d’art whose petals bloom and close at 24-hour intervals. Hand engraved with hemp leaf patterns on both its dial and caseback, this 42mm white gold timepiece features a perpetual moonphase and Edo Kiriko-style engraving, and Makihara will only make one example of Beauties of Nature each year.

After all, Makihara is a busy man—he’s been a full-fledged member of AHCI (L’Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants) since 2022, and also teaches at his alma mater, the Hiko Mizuno College of Jewelry.

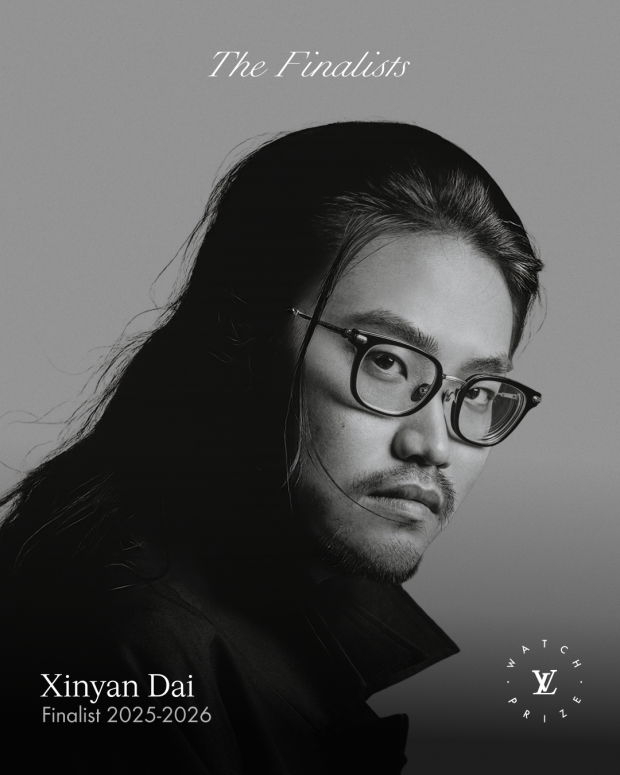

Xinyan Dai of Fam Al Hut

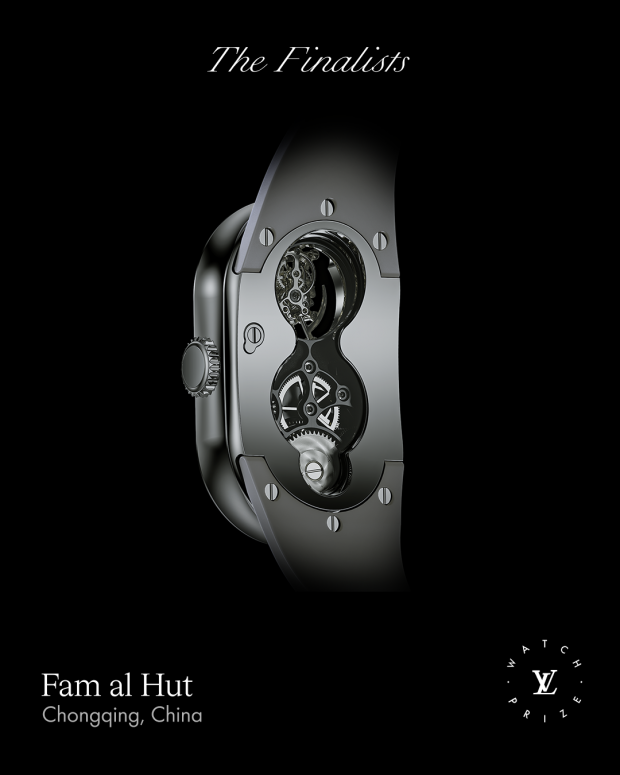

Named after Fomalhaut—the extraordinarily bright star in the Piscis Austrinus constellation—Fam Al Hut was barely a year and a half old when it clinched the Audacity Prize at the 2025 Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève.

Founded in May 2024 by Xinyan Dai, a voracious collector who studied art in Italy, and Lukas Youn, who worked in Europe and is fluent in both English and German, Fam Al Hut announced itself with audacious confidence. Its headline-grabbing debut was an openworked bi-axis tourbillon wristwatch paired with double retrograde displays—an improbable feat for a brand so young.

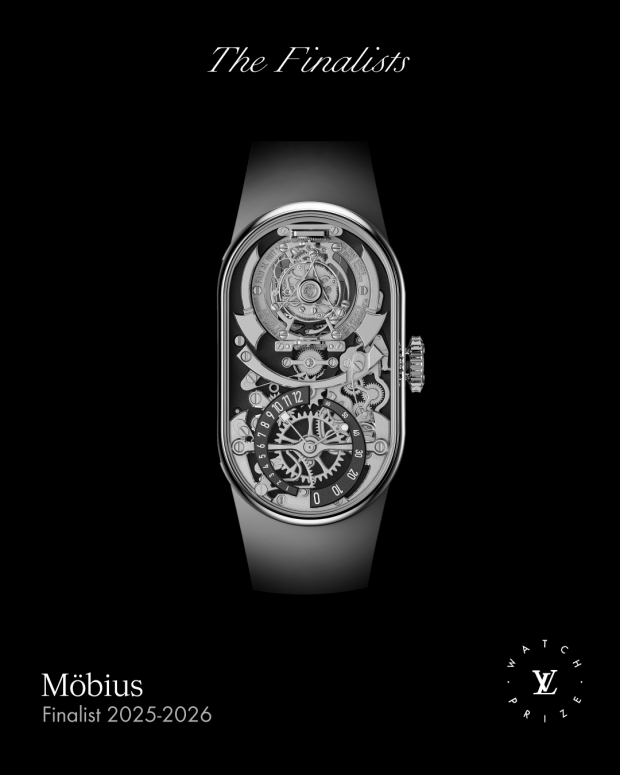

Named after the Möbius strip—a one-sided loop of infinity you might remember from Avengers: Endgame—the Fam Al Hut Möbius adopts an elongated architecture to accommodate a remarkable density of complications. In its upper register sits a bi-axis tourbillon: not a three-dimensional flying tourbillon, but a tourbillon that rotates on one axis every 150 seconds (90 seconds in production models) and on a second axis every 60 seconds.

The lower half of the dial is devoted to time indication, where hours and minutes are displayed on elliptical tracks via retrograde pointers, with the hour hand incorporating a jumping mechanism for added theatricality.

Powering the watch is the in-house, manual-winding M-01T caliber, housed in a steel case measuring 42.2mm by 24.3mm. For an additional USD1,000, the case can be upgraded to ultra-tough amorphous zirconium—a type of bulk metallic glass formed by rapid cooling, which prevents atoms from settling into a uniform, malleable pattern.

Despite requiring over 200 hours of handcraftsmanship, the steel version of the Möbius Mark I is priced at a strikingly accessible USD32,000. Demand, however, has been swift: Fam Al Hut’s waitlist now stretches beyond two years. Those willing to exercise patience are rewarded with a timepiece that conforms comfortably to the curvature of the wrist, meticulously polished and treated with anti-reflective coating to ensure it dramatically captures light.

Propelled by the indefatigable efforts and international success of maisons such as Atelier Wen and Fam Al Hut, Chinese watchmaking is rapidly earning global reverence. Widely regarded as the most complicated mechanical watch ever made in China, the Möbius Mark I encapsulates Dai’s and Youn’s vision for a new era of Chinese haute horlogerie. Encircling the bi-axis tourbillon is a discreetly engraved plate that distils this ambition into a single line: “All that exists was once imagined.”

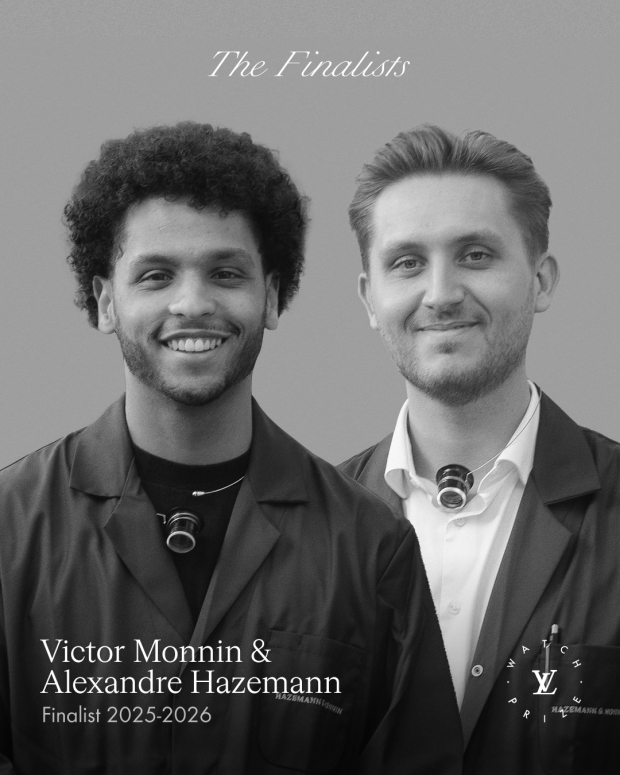

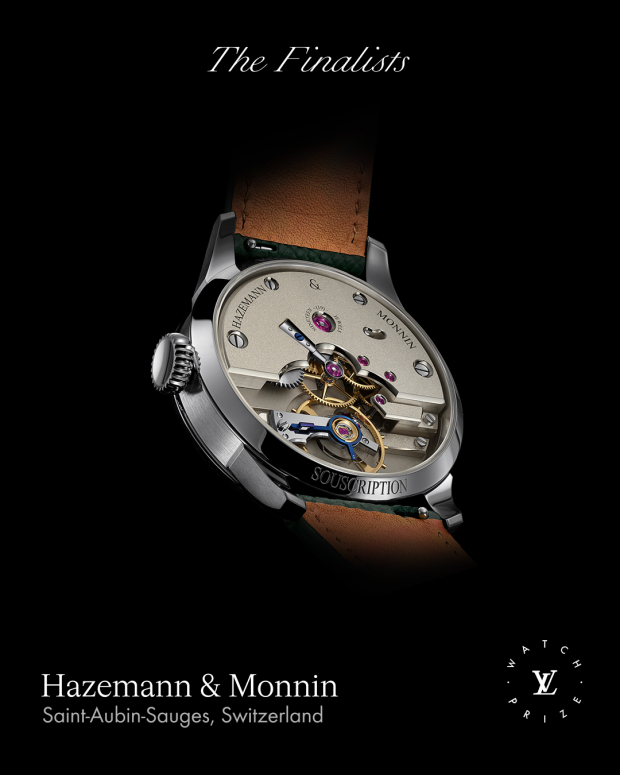

Alexandre Hazemann and Victor Monnin of Hazemann & Monnin

If haute horlogerie were a major league sport, you could say that Alexandre Hazemann and Victor Monnin are the undisputed first-round draft picks of their year.

The two Frenchmen met at the Lycée Edgar Faure in Morteau, France, where they bonded almost immediately over an unquenchable passion for watches and a shared reverence for discipline at the bench. Their mutual admiration for each other’s work ethic soon evolved into a rare creative symbiosis.

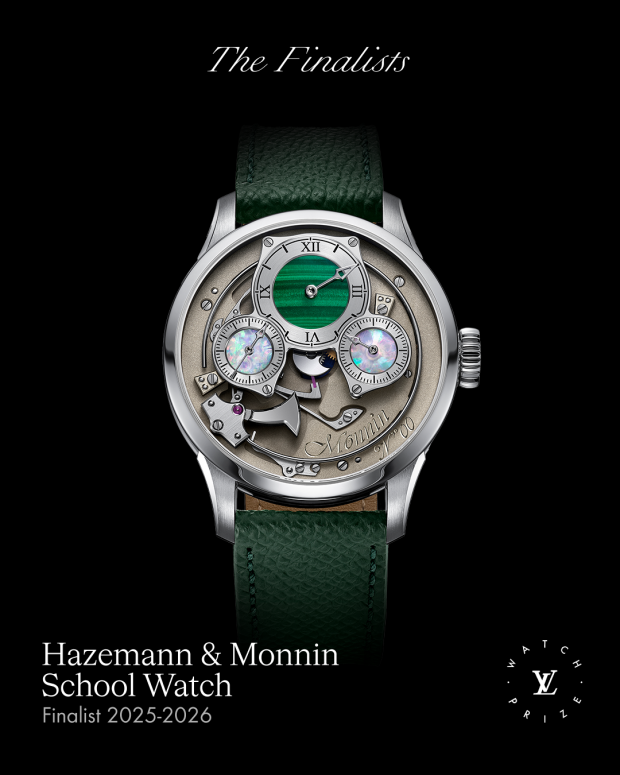

The Edgar Faure watchmaking school—alma mater to modern luminaries such as Rémy Cools and Theo Auffret—will long remember the moment Hazemann and Monnin unveiled their seventh-year project: the School Watch. Measuring 39.5mm, the jumping hour wristwatch synchronizes each instantaneous hour change with a sonnerie au passage chime, its name a deliberate tribute to the institution that shaped them.

Thanks to the school’s partnership with Arnold & Son, promising students like Hazemann and Monnin are granted access to complicated ébauches by La Joux-Perret (Arnold & Son’s sister manufacture within the Citizen Group), offering early exposure to high complications.

Both laureates of the F.P. Journe Young Talent Competition also hail from watchmaking lineages. Hazemann’s father worked closely with Michel Parmigiani, while Monnin’s grandfather and great-grandfather founded Georges Monnin—a company instrumental in helping to rescue Heuer (which was subsequently absorbed by TAG Group and named TAG Heuer) during a precarious period in its history.

Their development was further shaped by an enviable circle of mentors, including Simon Brette, Sylvain Pinaud, and Julien Tixier—then only a few years their senior—as well as master watchmaker Emmanuel Bouchet, best known for his work at Harry Winston. Unsurprisingly, their personal pantheon includes Patek Philippe, François-Paul Journe, Maximilian Büsser, and the godfather of modern hand-finishing, Philippe Dufour.

Few watchmaking students would dare to tackle a chiming watch—one of horology’s most revered complications—as a school project. Hazemann and Monnin did exactly that. Not only did they develop an entirely new movement, the HMO1, for it, but they conceived, manufactured, assembled, and finished it in-house, without leaning on pre-existing architecture.

In just eight months, the product of sleepless nights, meticulous calculations, and weekends spent behind the bench emerged: a sonnerie au passage timepiece with a 50-hour power reserve and a clarity of chime that belies its student origins, standing shoulder to shoulder with the work of horology’s titans.

Each watch bears subtle personal distinctions. Hazemann’s version features heat-blued hands and screws, while Monnin’s is marked by a striking green malachite center.

Now, having returned from specialized studies in different disciplines of watchmaking, the duo are reuniting—to the delight of collectors—to produce limited runs of fully handmade timepieces under the Hazemann & Monnin name.

Bernhard Lederer of Lederer

Bernhard Lederer submitted a more compact iteration of his tour-de-force Central Impulse Chronometer (CIC), distilling one of contemporary watchmaking’s most intellectually ambitious movements into a wearable 39mm format. The CIC presents the first fully functional dual detent escapement ever realized in a wristwatch, built around two independent gear trains, twin escapement wheels, and dual remontoirs d’égalité that ensure constant, balanced energy delivery to the regulating organ.

This architecture—rooted in the lineage of Breguet’s natural escapement and refined far beyond its historical limitations—allows impulses to be delivered alternately and symmetrically, dramatically improving chronometric stability while reducing friction.

The CIC 39 Racing Green is housed in a 39mm case measuring just 10.75mm thick, a remarkable feat given the movement’s complexity. Its COSC-certified calibre is 98 per cent manufactured in-house, underscoring Lederer’s rare vertical autonomy—from escapement components to bridges—and reinforcing his reputation as one of modern horology’s most rigorous thinkers in precision engineering.

Norifumi Seki of Quiet Club

Long-time friends HK Ueda and Johnny Ting spend no small amount of time dissecting other people’s watches—debating design choices and musing over what they might have done differently. One day, almost in passing, Ueda asked Ting whether he would ever consider creating a watch of his own. The question lingered, setting the gears in both their minds in motion.

In search of a movement specialist who shared their ideals, they were introduced to Norifumi Seki, himself a laureate of the F.P. Journe Young Talent Competition. Seki’s journey into watchmaking began at 17, when he saved up from part-time work to buy his first mechanical watch. That purchase led him down a rabbit hole of horological study—devouring George Daniels’ writings, immersing himself in technical literature, and eventually apprenticing under a watch restorer to hone his craft.

These formative years culminated in the pocket watch that won him Journe’s prestigious competition. The piece was remarkable not just for its spherical moonphase, but for its ingenuity: date displays driven by rotating drums rather than flat discs, and a balance wheel made entirely by hand—a painstaking undertaking that fans have attempted to purchase from him.

Given the international attention Seki received following his win, Ueda and Ting had to work patiently to win over an understandably cautious collaborator. When the trio finally aligned, they founded Quiet Club. Their debut creation, Fading Hours, is a quietly subversive chiming watch—one that literally strikes its own dial to sound an alarm.

Conceived and handcrafted entirely in Tokyo, Fading Hours features an additional pair of alarm hands discreetly hidden beneath the hour and minute hands. Housed in lightweight titanium for everyday comfort, this 40mm watch employs a single pusher to set, start, and stop the alarm, underscoring its emphasis on intuitive use.

Believing that many contemporary complications have grown detached from modern life, the trio set out to invent one that would genuinely enrich it. As habitual deep workers themselves, their thinking gravitated towards focus and concentration. While smartphones can sound alarms, they argue, such devices inevitably usher in a torrent of distractions. Fading Hours was conceived as the opposite: a chiming watch designed not to interrupt, but to gently guide its wearer with a pleasing melody into a deeper state of concentration. In that philosophy lies the quiet conviction behind the name Quiet Club.

SIGN UP

SIGN UP