The Timepiece ‘Changing Patek Philippe History’ Set for Christie’s Auction

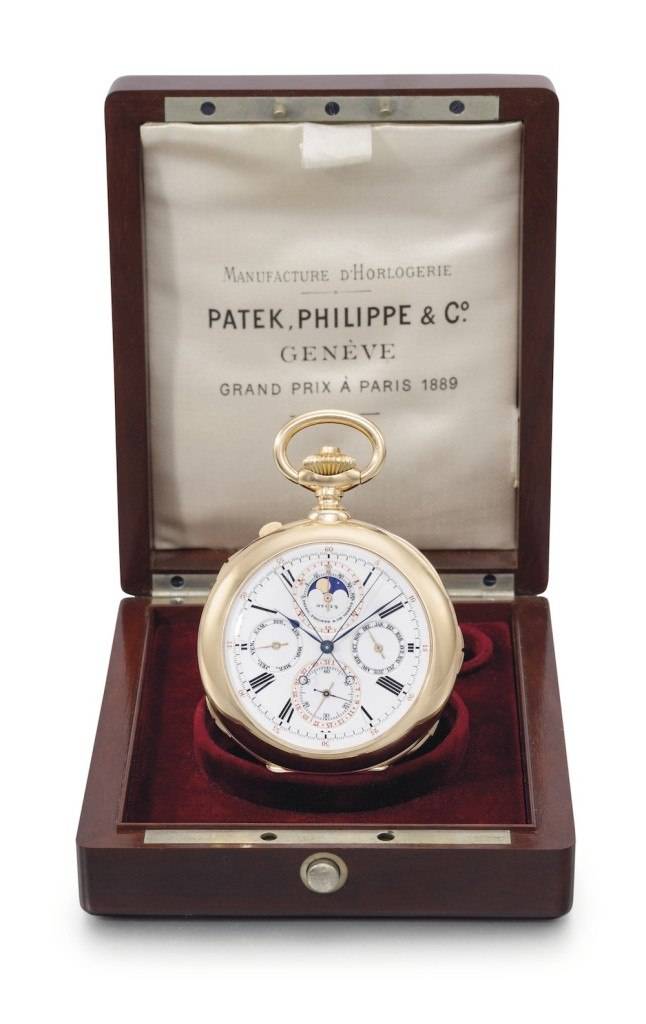

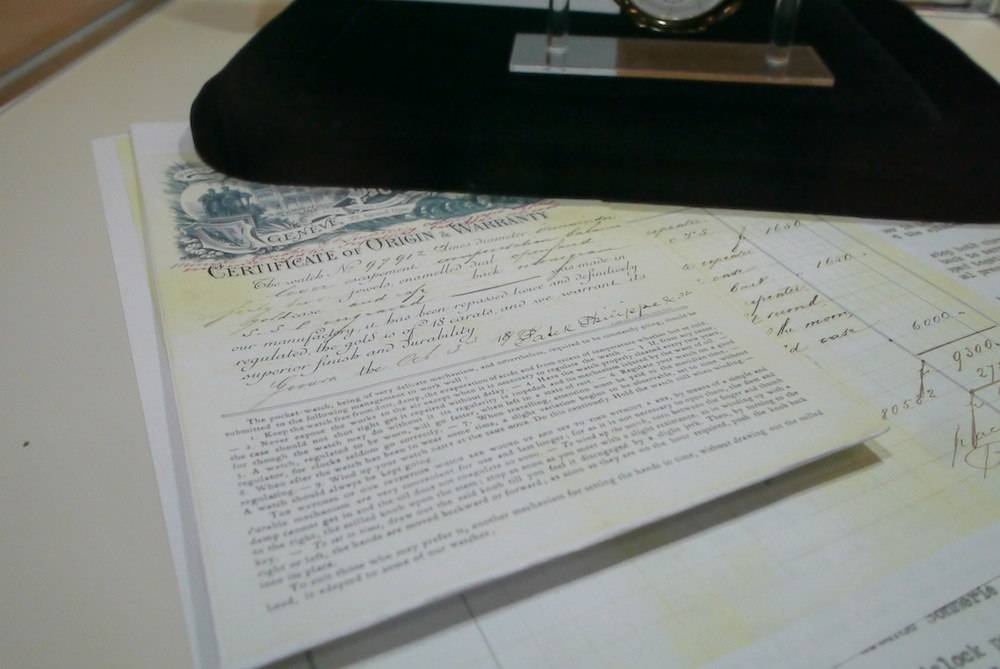

Earlier this year, Haute Time got a world exclusive first look at the Stephen S. Palmer Patek Philippe Grand Complication, No. 97912. We spoke with Aurel Bacs, the International Head of Watches at Christie’s Auction House, for the scoop on this recently discovered timepiece, a gold openface minute repeating perpetual calendar split-seconds chronograph clockwatch with grande and petite sonnerie and moon phases. Accompanied by an original certificate and invoice dating back to 1900, this timepiece is already being described as changing the history of Patek Philippe.

With the Christie’s “Important Watches” auction set to take place on June 11 in New York City, we wanted to revisit this extraordinary timepiece. We have your close-up look at this clockwatch, details on the American business magnate being described as the new Henry Graves, and feedback on what Patek Philippe think of this historic discovery.

Haute Time: This clockwatch has been described as re-writing the history of Patek Philippe. What can you tell us about this extraordinary timepiece?

Aurel Bacs: What I believe is that scholarship, when it comes to the history of ultra-complicated timepieces, is changing because of this watch. When we look at Patek Philippe today – and I believe wholeheartedly all collectors and scholars will agree – no name in the last two centuries can be associated to the same extent as Patek Philippe to complicated watches and ultra-complicated watches. When I ask my collectors, clients – why is that? Why is Patek Philippe the synonym of mastering complications? Most of them say, well look at all the watches they’ve made, and look at the super complications they made for Henry Graves, for example – the man whose watches, when they come rarely to the market, give multi-million dollar hammer prices. So is it all down to Henry Graves? Well no, because before Henry Graves, there was James Ward Packard, the automobile manufacturer who was collecting about two decades ahead of Graves. So basically, should we thank Mr. Packard for bringing Patek Philippe to make these ultra complicated watches? There were other clients before but nobody at any comparable level than these two gentlemen who pushed Patek Philippe to levels that – it is just a blessing from the heavens that Patek Philippe accepted to be pushed to these levels. Because when you’re pushed, you can either accept the challenge or reject. But if you don’t accept it then obviously nothing comes out of it.

One day, we were offered this watch – a watch that was never seen or shown in literature before. The Patek Philippe books have really nearly exhaustive numbers of illustrations about the most complicated pieces the brand has ever made. This watch is not in there. It wasn’t because since 1900 when it was made – it was nowhere published, nowhere described, nowhere offered at auction, there were no traces of it. The last trace – that is not publicly accessible – is in Patek Philippe’s archives from 1900, where the workshop books list the making of the watch.

So we come to the history of the watch. This watch was made at the end of the nineteenth century, and sold in October 1900 to a Mr. Stephen S Palmer. We have the original invoice – which is already a rarity in itself – that says Mr. Palmer was in Geneva in October 1900, staying at the Hotel Beau Rivage, and bought from Patek Philippe not just this watch, that is wonderfully described on the invoice, but another two complicated watches. A gentlemen who buys three complicated watches is not just someone who is looking for a timepiece to tell the time. They’re not a first time buyer. On top of that, he gave back another complicated piece as an exchange – part exchange – against the new purchases. So he already had Patek Philippe watches before.

It leads us to an observation that this man was looking for more than just a watch. The fact that his watches were all engraved with his monogram SSP – that is confirmed on the certificate and the invoice – is another hint that he wasn’t just walking into the shop and saying ‘Hello I’d like to buy a nice watch.’ Because you cannot engrave such a beautiful monogram in one day over a lunch break. You had to pre-order that. So there is more depth and history in his doing and his collecting than just ‘oh I’m in love thank you I’m buying it’.

But most importantly, this was, in 1900 – as far as we know today – the most complicated Patek Philippe ever made until that point. A title previously held by the Graves and the Packard watches made in the 1910s, 20s and 30s. So now we anticipate everything by a decade at least, and suddenly discover that there was this Mr. Palmer, of whom there was no mention in horological literature. So who was this Mr. Palmer?

Mr. Palmer was one of the leading businessmen of late 19th and early 20th century America. A man who can be put in the same league as Cornelius Vanderbilt. A man whose businesses – I’ve seen the list and it was just an exhaustive list of all business that made good profits in 1900; zinc, copper, steel, banking, lending, insurance, construction, railways – everything needed if you wanted to make a huge fortune. Those were the businesses that are the reason why the 20th century became the American century. The biggest wealth was created here in America by people like Stephen Palmer.

Stephen Palmer and his family were in the history of Princeton, as far as I understand, the largest family donors to Princeton University. [The town of] Palmerton is named after the Palmer family. One of the families that were not just occasional – ‘I like to have a watch’. They were at the very top, in America’s business history, and since the discovery of this watch, in the history of horology. Until then, there were minute repeaters, perpetual calendars, a chronograph – maybe even a clock watch. But no watch that had everything together. This is, in my view, one of the founding stones of where Patek Philippe started their path of success and mastering complications. Patek Philippe is at the top of the game today – and this could well be the point of departure, the catalyst.

It is a privilege, after having sold watches of Graves’, having set records for Packard watches, that now we have this watch and all its documentation – not just the privilege to research it, but also to offer it for sale. It’s really the most exciting watch worldwide to come to the market this Spring season.

HT: This must also open up for you a new venue of discoveries to be made. Do you anticipate big lots like this coming from Palmer’s collection in the future, or is this a one-time discovery?

AB: There’s always a hope that there’s going to be a grandson or great-grandson of Palmer’s who will come to us and say, ‘I’ve also got a watch from my grandfather or great-grandfather’. We already know that the watches on the invoice here – we don’t know where they are. They’ve never been on the market. We’ve X-rayed 40 years of watch auction markets, and none has appeared. They must be somewhere, with someone, so this watch opens up a brand new chapter. The next Patek Philippe book must dedicate a chapter to Palmer and that is what I call rewriting history. We’ve added a brand new element to their history that was not known to even the most educated scholars.

HT: Have you had any feedback from Patek regarding this find?

AB: Mr. Stern or Patek Philippe have not yet been informed by us, because there is no press release out yet for this. It’s not been catalogued yet, so this is a scoop! But we will be in touch with Patek Philippe to also give them the pleasure of rediscovering this watch, of course.

HT: Early estimates for this piece are between US$1,000,000-1,500,000. What do you anticipate the bidding war will look like for this piece?

AB: It’s too early to anticipate the bidding war, because not a single potential buyer has seen it yet. This is brand new – the exhibition hasn’t even opened yet, the catalogue is not out, the press conference hasn’t taken place yet. So, it’s absolutely too early to anticipate. I wish – because the watch deserves it – that multiple collectors from different continents will fall in love, as our team of specialists did, and that they will have the willingness to open up their wallets and bid fiercely. I hope it ends up in the hands of someone who loves that watch and respects that watch the way we think it deserves to be respected.

HT: There seems to be a wider trend of increased attention on the vintage timepiece market. Do you feel that increased interest?

AB: I certainly feel it. We had, last year, with $130 million, the strongest year any auction house ever had in the field of horology. Think about 2012 – we’re not associating 2012, as such, with a booming economy. So to achieve these results is really of quite some magnitude. Why is that? First of all, the field of horology as such is on a growth. Meaning, the planet that has always considered a watch simply just a useful instrument to tell the time – more and more appreciates that the watch is a work of art. Secondly, it was Europe and America that for centuries were the only two continents showing interest in watches. With markets opening up – like China, India, Southeast Asia, Brazil, Middle East, Russia – that adds up. These countries add up to over 50% of the world’s population. And the one thing they all have in common – that Europe and North America do not have in common with them – is incredible economic growth. So there’s a huge number of new collectors coming to the market.

I love contemporary watches that are made today, but I must admit that I love even more vintage pieces for one simple reason. It’s like – a painting is one two dimensional, a sculpture three dimensional. A contemporary watch is two dimensional, a vintage watch is three dimensional – because it has the depth of time, the history. That results in stories like the Palmer. It tells you a story – we human beings, we have gray hair, we have wrinkles. That’s why a face is interesting. Babies look all the same! Whereas the 60, 70, 80 year-old woman or man has a face that tells a story. That is that other dimension that vintage watches have. So I am not surprised that the vintage arena and the auction arena are enjoying huge success these days. With Christie’s as the market leader, I can just sense the pulse of the market, and I assure you this is still growing – we haven’t yet reached the peak.

The Stephen S. Palmer Patek Philippe Grand Complication, No. 97912 will be part of Christie’s “Important Watches” auction taking place on June 11, 2013 in NYC. For more information please visit the Christie’s website. On-location photos by Valerie Jack. Additional photos: credit to Christie’s Images Ltd. 2013

SIGN UP

SIGN UP